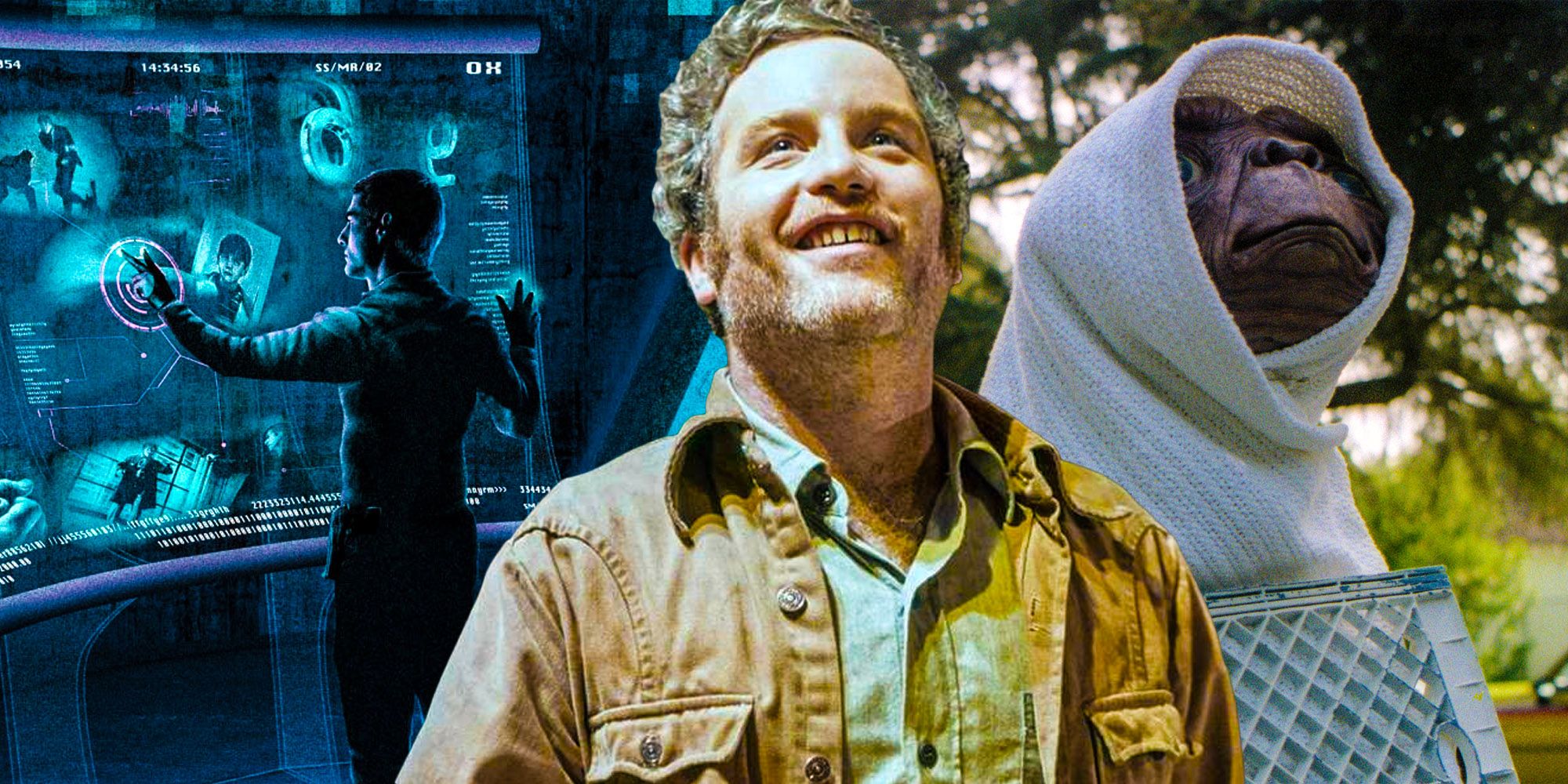

Steven Spielberg has crafted films in almost every conceivable genre, but how do his sci-fi films rank from worst to best? From 1977 to as recent as 2018, he has consistently returned to the well of science fiction as a source of spectacle, as a playground for cinema's latest technological advances, and as a prism through which to filter some of his most personal works.

Spielberg's big break came when he directed Jaws in 1975. The film set the domestic box office record at the time, was a critical success, and earned the filmmaker his first Best Picture nomination at the Academy Awards. Immediately after, Spielberg set his sights to the stars, directing Close Encounters of the Third Kind and, soon after, E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial. His mastery of the science-fiction genre stuck, and for the rest of Spielberg's extensive career, whether he was inspiring dinosaur-based terror in Jurassic Park or giving audiences something more moody and cerebral with A.I. or Minority Report, it's never been too long before he's come back for more.

From the genre-defining spectacle of Close Encounters to the recent CGI overflow of Ready Player One, Steven Spielberg has proven one of sci-fi's most important directors. Here are his sci-fi films, ranked from worst to best.

For most of the 2010s, Spielberg seemed to have totally distanced himself from the high-flying, kid-at-heart entertainment that dominated his early career. Instead, the director focused on trading in nuanced, complicated looks at American history like Bridge of Spies or Lincoln, which originally starred Liam Neeson. As such, when it was announced he'd be adapting Ernest Cline's best-selling novel about a future so brutal it's forced society to escape into virtual reality, there was a lot of excitement and anticipation to see him return to his "popcorn fare" roots. Alas, Ready Player One is a lot of empty spectacle, with its director showing little interest in bringing any sort of emotionality to its rote plot and instead surrendering wholeheartedly to a lot of long-winded, CGI action sequences absolutely overflowing with IP. As a condemnation of our nostalgia-obsessed society, this could have been interesting, but Spielberg is too busy treating it like his own big-budget playground. Unfortunately, aside from a mid-movie sequence that recreates The Shining's Overlook Hotel, this is a shockingly joyless affair.

Spielberg doesn't really do sequels, and when he does they're usually typified by an over-amplification of the excesses of the original, with more and more diminishing returns. That's certainly the case with The Lost World, which was the first Jurassic Park follow-up to learn that it's hard to keep the "dinosaur park gone wrong" formula fresh. There's none of the initial wonder here. Despite appearances by Julianne Moore and Vince Vaughn, there's not much in the way of interesting characters either. Jeff Goldblum, so neurotically hysterical in the original, is upgraded to leading man with mixed results, and aside from a hackneyed environmental message, Spielberg is mostly using this as a way to have a little fun when he sets a T-Rex loose on San Diego. It's all very silly and ridiculous without Alan Grant and Ellie Sattler, but a plentiful reminder of the director's skills at constructing some of cinema's most playfully engaging action setpieces.

Many Spielberg fans and critics have lumped this film, along with 2004's The Terminal and 2005's Munich, into an unofficial trilogy focused on America's mood post-9/11. While the former is more heartwarming and the latter more awards-focused, War of the Worlds transcends both, and the "trilogy" moniker, to become one of the most harrowing and definitive American films about that terrible day 20 years ago. Genre be damned, Spielberg is entirely unburdened by the pulpy sci-fi packaging the H.G. Wells classic could entail. There's none of the adventure of Jurassic Park, none of the good guys vs. the monster thrills of Jaws. This is first and foremost a film about fear and terror, from a river overflowing with corpses to the underrated and creepy Tripod monsters, and Spielberg laces his tale of a country faced with an overwhelmingly devastating invasion with a stripped-down, bleak parade of nightmare imagery. It may still be Tom Cruise's highest-grossing domestic film, but it's also the one where he has a full-on panic attack realizing that the ash covering him came from the disintegrated people he just ran through. Critics may deride its abrupt deus ex machina ending (although the idea of a virus wiping out a species is a bit more palpable in 2020), but this is quietly one of Spielberg's most terrifying and powerful films.

The 9/11 connection doesn't end with War of the Worlds. It is true that Spielberg's adaptation of the Minority Report story was filming long before September of 2011, but its depiction of societal paranoia and surveillance, where futuristic cops can arrest people just for knowing they're going to commit a murder, hit the zeitgeist in a chilling and downright uncanny way. A lot of that has to do with its source material, a 1956 novella by Philip K. Dick, whose works have inspired other sci-fi masterpieces like Blade Runner and Total Recall. However, the movie is exceptionally different from the book, and it's Spielberg, along with Janusz Kaminski's washed-out future-meets-noir cinematography, who realizes the story's ultimate screen potential. The early 2000s saw Spielberg marrying his genre mastery with a disillusion with the optimism which was his trademark through the '70s and '80s. Minority Report, anchored by a typically sturdy Tom Cruise performance, is as thrilling a pulpy, man-on-the-run flick as it is a muted screed against an America abandoning its principles.

1977 was a banner year for science fiction in film, with defining efforts from George Lucas and Steven Spielberg completely reigniting the genre and paving the way for the types of movies made to this very day. However, if Star Wars was a zippy romp through space, a fairy tale-Western mashup about good and evil, dashing heroes, sassy princesses, and laser guns, then Close Encounters of the Third Kind was a more serious-minded, majestic affair, with Spielberg mulling on a sequel after its success. It's as much a film about childlike wonder as any Spielberg has ever made, but there's a mysterious, haunted quality to its view of the extraterrestrial. It's one of the filmmaker's slowest, coldest, and most cerebral films, but its tale about an obsessive man building models in his kitchen and attempting to connect to some cosmic force larger than himself is also in many ways a snapshot of his entire career. The final sequence stands as one of his most defining, a visual and aural symphonic depiction of two species communicating that could only be delivered by a master. With the iconic and quotable Jaws, Spielberg turned pure pulp into a blockbuster, but with Close Encounters he made clear his desires to transcend genre trappings and reach for the stars.

Without a doubt one of the most polarizing entries in Spielberg's entire filmography, A.I. Artificial Intelligence has rightfully been getting a slow and steady reevaluation in the 20 years since its release. This cracked glass slipper of a fairy tale was not the return to sci-fi that audiences perhaps expected or wanted from the director in 2001, but it fits more comfortably in a lineup that now includes similarly bleak genre outings like Minority Report. Additionally, initial criticism which insisted on bifurcating the film into "Steven Spielberg parts" and "Stanley Kubrick parts" (Spielberg and Kubrick developed this film together for years prior to Kubrick's death) can now largely be dismissed as utter nonsense.

While A.I. is overflowing with the cold unease of Kubrick's work, this is a Spielberg film from beginning to end. In fact, one could argue it's the hub that connects the man who made Jaws and Raiders of the Lost Ark with the one who made Lincoln and Munich. It's a haunted subversion of the childlike wonder of his early films; Haley Joel Osment's David an eerie, funhouse mirror version of Henry Thomas' Elliott. Anyone who watches this film and says its ending devolves into heartwarming sentimentality isn't paying attention; the final image Spielberg conjures is a jagged hug, and one of his most chilling and disturbing.

There's so much good to unpack about Jurassic Park, whether it's the groundbreaking technical and CGI innovation, the iconic John Williams score, or the still mindblowing fact that it released the same year as another of his all-time masterpieces, the polar opposite Schindler's List. 1993 represents a prime snapshot of the incomparable versatility of Spielberg, but Jurassic Park marks the last time, to date, that he made a big, playful blockbuster that can also be counted among his best works. At its heart a Frankensteinian parable about hubris, Jurassic Park begins as another Spielbergian masterclass in childlike wonder, before it pumps the gas, lets the dinosaurs run amok, and becomes one of cinema's most exhilarating rollercoaster rides. Some of the director's most unbearably tense work is on display here, from the introductory scene of the T-Rex to the endlessly-mimic'ed kitchen scene with the terrifying and oft-changed Velociraptors. A fifth sequel is due for next year, but nothing will ever beat the original.

E.T. is the defining film of Steven Spielberg's career. It begins with Melissa Mathison's screenplay, which tells the story of a suburban boy who finds an alien in his barn and decides to shelter it from harm. It's Spielberg, however, who transforms this simple concept into one of cinema's most primal tales of friendship. Everything in this film feels alive, from its dynamically staged opening scene of a single mom trying to corral her smart-talking kids and order a pizza, to the remarkable puppetry that gives the titular character its soul. Henry Thomas' raw turn as Elliott is arguably the greatest child performance in film history, and John Williams' iconic score is the film in a nutshell: a delicate flower which blossoms into a a magnificent work of soaring emotion. To watch E.T. is to surrender to the full power of a cinematic master who has always understood that sometimes a genre filter can be the best way to get to a universal truth. In the final act, Spielberg wrings every conceivable kind of tears from his audience, as the movie careens seamlessly from devastation to elation, from fist-pumping joy to a remarkably powerful feeling of loss. E.T.'s brief time on earth teaches Elliott, and the film's audience, how to love and, when the time comes, how to say goodye. "I'll be right here," he says, and it's true. E.T. is one of cinema's most timeless classics, and it will be around for generations and generations to discover.

from ScreenRant - Feed https://ift.tt/3yBFUkc

No comments: